Buried In Silence: Chasing the American dream

HCC student, Susana Matta, opens up about the realities of living as an unauthorized immigrant in the United States.

October 28, 2019

Susana Matta has always been good at keeping secrets.

Since she was 6 years old, her parents told her the slightest slip of the tongue could lead to the end of their livelihood. So, she kept quiet.

Her friends would often ask why she was so hesitant to partake in their reckless endeavors — why she lived in constant fear despite growing up in the home of the brave.

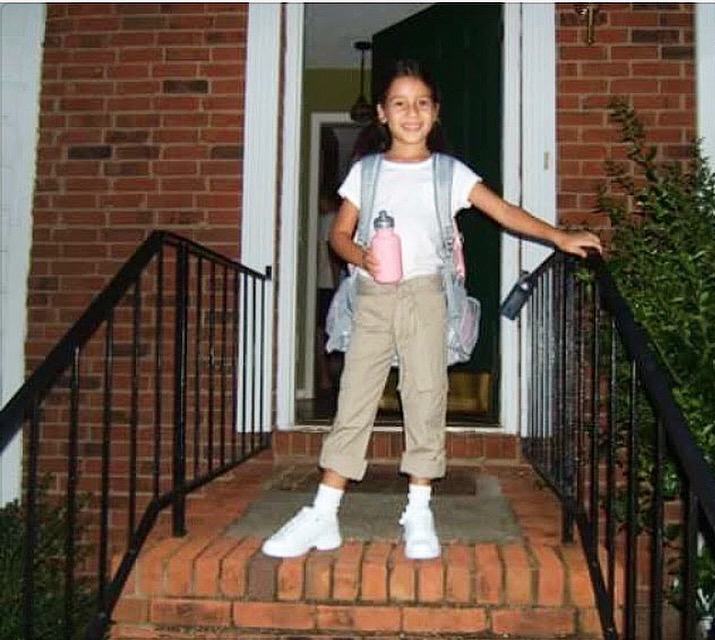

Matta, age 6, on her first day of school in the United States.

The answer to those questions was simple: Matta’s parents dreamed of giving their children a better life, and they tried their hardest to ensure that — even if that meant they had to harbor a secret.

Back in Colombia, her family struggled to keep their heads above water. The economy was plummeting, and ordinary life grew increasingly dangerous with each passing day.

They had been comforted by the alluring image of white picket fences and captivated with a place full of limitless opportunities.

The thought of the American dream seemed too good to be true, however, and ultimately it was.

Matta and her family, like the other 11 million unauthorized immigrants living in the United States, never enjoyed the luxuries of the suburban middle-class.

Instead, they lived in poverty: a decrepit two-bedroom apartment riddled with roaches and spiders.

“Because of their legal status, it is tough for them to grow beyond where they are, which is the most terrible part of all because they are very hardworking people,” Matta’s friend and fellow immigrant, Annais Becerra, said.

Out of fear of deportation, Matta’s parents, who had both completed high school and undergraduate degrees in Colombia, worked menial jobs with little pay. Her father worked as an ice cream man while her mother cleaned houses.

Without a proper form of identification, a social security number or a valid driver’s license, there remained few alternatives for housing or employment.

Among these limitations, Matta’s family often avoided visiting the hospital. Healthcare was unavailable to them, and visits were costly.

Matta remembers her father employing the help of a friend to remove two of his molars with pliers and over-the-counter oral anesthetic, rather than visiting a dentist.

“It was a constant struggle,” Matta said. “Despite being raised in a prosperous nation, many resources have always been completely withheld from me.”

While Matta has always appreciated her parents’ resilience, their inability to grow because of their legality has often left her feeling hopeless. Having been raised in the United States, Matta views herself as an American and believes their hard work should allow them equal opportunity.

“I don’t think your legal status or country of origin should determine your quality of life,” Matta said. “[My family] worked hard to become as American as possible, but we aren’t. We feel like we are, but everybody else doesn’t see us that way.”

Since 2016, the public distaste for immigration has grown more vocal. While the Obama administration prioritized deporting immigrants who committed more severe crimes, the Trump administration has issued new policies targeting immigrants who commit minor offenses such as driving without a license.

After applying for permanent residency in 2007, it has been a waiting game for Matta and her family.

“All I can do is expect the worst. I have all of my mom’s passwords for her bank and every important document. I have all the important numbers in case something does happen,” Matta said.

Despite these pitfalls, the Mattas managed to make a life for themselves. Though the task proved to be a jarring and challenging experience, Matta’s parents stand by their decision.

“I have struggled very much in this country, but I would have struggled more in Colombia,” Matta’s mother, Diana Patricia, said. “The same way many people don’t want me here, many people have been nice to me. Those people are the real Americans.”

The permanent residency case for Matta’s family has been processing since Jan. 4, 2010.

Summerlin • Feb 4, 2020 at 11:52 pm

This was beautifully written and the picture helps bring it all together.

Elliot Breheny • Feb 4, 2020 at 10:47 am

I feel as though many people who were born and raised in America aren’t aware of what immigrants go through to become a citizen. This story is raw, and shows the reality of the struggles someone such as Susana can encounter. People who are try to make immigration harder need to take the time and look at who these people are and where they are coming from. No one is trying to take advantage of our resources, they’re just trying to have a better life.

Chloe Zentkovich • Nov 21, 2019 at 8:24 pm

This really sheds light on the struggles of unauthorized immigrants. For me, I was born free in the United States and never experienced the fear of my family getting deported. I can’t imagine living another way as a child. Constantly being in fear of returning somewhere that kept you in poverty sounds like a nightmare. I hope soon we can make changes to this and give all immigrants an easier way to become citizens.

Jaliyah White • Oct 29, 2019 at 5:18 pm

I completely agree with you. I don’t believe your country of origin or legal status should determine the quality of your life. You’re human at the end of the day, just like us. I am so proud of you girl!