Buried In Silence: How the other half lives

HCC student, Susana Matta, shares her trials and triumph as an unauthorized immigrant in the United States.

March 25, 2020

MIAMI — Juan was arrested today, Susana Matta wrote in her journal, shifting in her seat as though uncomfortable with sitting still. This is my worst nightmare and my most joyful dream clashing together.

The walls of the Roxcy Bolton Rape Treatment Center were devoid of life. All the same, Susana stared at them intensely, memorizing the places the paint was chipped — anything to pass the time, to keep her from going mad.

The physicians hadn’t let her change her underwear yet, and the feel of the cold metallic seat only furthered her discomfort.

Susana hadn’t entirely sobered up from the copious amounts of vodka she was forced to drink. Her head throbbed and her tongue felt as if it were stuck to the roof of her mouth.

She swallowed back a pool of saliva in an attempt to keep the moisture from ebbing away. Asking for water proved useless; “You could still have his DNA inside your mouth,” a physician would reason.

The crisp, sterile air made the hairs on the back of Susana’s neck stand up. She wrapped her arms around herself, clutched her hoodie and rocked back and forth in her chair to keep warm.

Her eyes drifted toward a window sill beside her, but all that stared back was darkness.

As she narrowed her vision on the dull view, she could almost see her reflection contrasting against the night sky.

At that moment, Susana was reminded that she had finally been given a clean slate.

She held tightly onto this hope that the suffering that dominated her past was now behind her.

Susana thought that night would be the end.

• • •

That was two years ago, on a summer night in August 2018.

Her memories of that evening remain a painful blur, as do many of the memories of her abuse.

Susana, 19, now attends Hillsborough Community College. Those who know her say she’s a kind young woman and a dedicated student.

They don’t see the bags under her eyes, the pepper spray in her purse or the way she always looks over her shoulder in fear of being followed.

They don’t know she juggled algebra tests and court hearings her last year of high school, or that she’s an unauthorized immigrant.

At first glance, Susana doesn’t seem much different than the students she walks among, though she knows that has never been further from the truth.

All it takes is the faint smell of sweat or an unexpected touch to send her flying back onto the bed of a rundown hotel.

She is one of an unreported number of unauthorized immigrants who have been exploited and silenced by their legal status.

Susana knew she wasn’t the first, and she knows she won’t be the last.

• • •

Susana was only 6 years old when she had to leave everything behind.

She didn’t understand then why she couldn’t bring all her toys with her or that she’d never see the crooked brick roads of Barranquilla, Colombia again.

All she knew was if anybody asked why they were going to the United States, she’d respond without fail, “we are here to go to Disney World and see Mickey Mouse.”

As she zipped by crowds of people bustling about the airport, she clutched her parents’ hands tightly. Susana couldn’t conceal her excitement.

She fantasized about her new school, all the friends she’d make and seeing her parents smile. The lies she’d have to tell felt like a rite of passage, her way of helping her parents with the big move.

So, no matter how mangled or incoherent each stutter made her broken English sound, she wore it proudly — unfazed by the confused expressions that met her responses.

When Susana’s family arrived in Marietta, Georgia, they carried nothing but a few cases of luggage and the burden of their homeland’s economic decline.

Susana’s parents looked at one another. Had they escaped the dangers of the guerilla movements in Colombia? Had they successfully avoided deportation? Had they found a place they could raise Susana safely?

As hundreds of self-deprecating thoughts began to flood their minds, their eyes met Susana’s, and in an instant, their concerns seemed to fade away.

Susana Matta, 6, photographed on her first day of school in America.

Every risk, every sacrifice would be worth it if they could give their daughter the future she deserved.

Susana’s parents looked at one another again, though a little more hopeful this time.

For years they had lived under a corrupt government, but now they held the opportunity to pursue the American dream.

They were welcomed by Susana’s maternal aunt, Angela Patricia, who offered up her home to them while they got on their feet. Within weeks of their arrival, Susana’s parents enrolled her at Sedalia Park Elementary School.

Dressed in ill-fitting khakis and a plain white t-shirt, Susana marched into the building, her velcro Sketchers screeching at every turn.

She didn’t pay mind to the critical eyes that followed her wherever she went; her parents had told her this was part of the process.

So, whenever she felt her knees buckle or her cheeks burning bright red, she reminded herself that eventually, things would get better.

“I was always grateful that we moved here,” Susana said, her smile fading with each word that followed. “I think my parents instilled that in me that I had to be grateful for absolutely everything, even if it didn’t feel good at that moment.”

• • •

The stench of tobacco lingered throughout the apartment complex, a result of the many cigarette butts scattered upon the ground like grotesque confetti.

The apartments were broken-down, distorted shadows of what they once were; each step inside made its foundation squeal as if the entire building would collapse.

All the same, Susana’s family thought the bleak and withered landscape was a sight for sore eyes.

They had searched tirelessly for housing and employment during their eight-month stay in Georgia, but each attempt was futile without established credit or a proper form of identification.

At the behest of their paternal relatives, Susana’s family gathered what little they had and moved to Tampa, Florida. It was there that they found a lease willing to turn a blind eye to their lack of documentation.

To avoid being deported, Susana’s parents, who had both completed high school and undergraduate degrees in Colombia, worked menial jobs with little pay. Her father worked as an ice cream man while her mother cleaned houses.

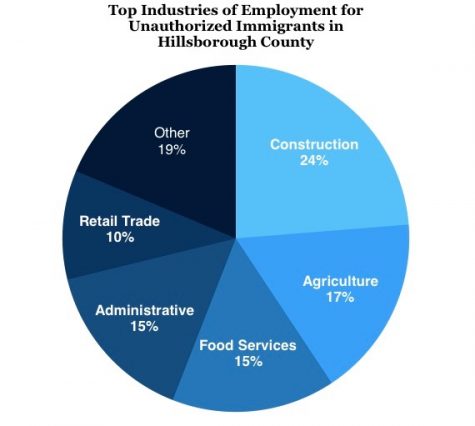

Data from the Migration Policy Institute.

They had hoped that their modest living situation would be temporary. After applying for permanent residency in 2007, it seemed as if their hard work had finally produced results.

However, as the months turned to years, Susana’s family became disillusioned by their inability to advance in their processing and their quality of life.

Nonetheless, Susana’s parents remained confident that the decisions they made long ago were for the best.

“I have struggled very much in this country, but I would have struggled more in Colombia,” Susana’s mother, Diana Patricia, said, wrinkling her forehead for emphasis.

This sentiment, however, began to wear itself thin with Susana as she turned 15 years old.

She couldn’t get a learner’s license, she couldn’t get an after-school job and with each passing day, a restlessness began growing within her.

Susana wondered if this was her fate: to stand there, watching her friends do all the things she never could.

So, after realizing that enrolling in the military would not only provide her with citizenship but other amenities she never possessed, like healthcare and the prospect of furthering her education, Susana joined her high school’s Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (JROTC).

She reminded herself time and time again that the tedious hours of practicing drills might be her only chance at a life she could feel satisfied with.

Still, the mere thought of fighting for a country that wasn’t fighting for her left Susana’s stomach in knots.

• • •

Susana had never seen a rapist before. She didn’t know what they looked like or what they might be wearing. She had never seen one pass by her on the sidewalk or at the grocery store.

She never saw a rapist — not even as one walked right into her uncle’s house on Christmas Eve.

It was 86 degrees. Florida’s usual pit-stain weather managed to stick around for the holiday season.

Susana sat on her cousin’s bed; together, she and her cousin gossiped and teased one another for hours.

She was happy to be out of school — two weeks without having to go to class and wearing that dreaded beige JROTC uniform.

For a brief moment, she was relieved of the stress of her pending citizenship. Susana let herself be a kid, even if it was just for a day.

Her lighthearted conversation, however, was interrupted when her older cousin, Juan Matta, entered the room.

His shoulders were broad; his back was arched in nearly perfect posture. His expressions made him seem sure of himself, and he spoke as if someone was clinging to his every word.

Juan, like any person, was multifaceted. To some, he was a father, a husband, a brother and a friend; to Susana, he was the epitome of everything she was not and might never be.

They never spoke much in the past. They were hardly ever seen in the same picture, but on that Christmas Eve, everything changed.

Juan had heard of Susana’s plan to join the military, and he took it upon himself, as a captain in the Marine Corps, to find out why.

He had a fixed gaze upon Susana as she explained where the idea had come from. He stood silent at first as if he had just received bad news.

After correcting her statements about the military, a feat Juan couldn’t resist, he mentioned that if someone adopted her, they could petition for her citizenship.

A few days later, much to Susana’s surprise, Juan offered to do so himself. Suddenly, the solution to all her problems seemed to have arrived in the form of a family member extending a helping hand.

The offer seemed too good to be true, and ultimately it was.

• • •

When the Hialeah Police Department responded to a call that a potential rape was in progress, they had no idea they’d be late.

By the time they arrived at the hotel, Susana had already been stripped of her clothes and her dignity.

Juan had seen the police entering the garage and hurried to get Susana dressed so they could leave quickly. They had already reached his car when officers approached them.

Susana vaguely remembers the way he struggled to answer why he was leaving a hotel with an intoxicated minor in the backseat; however, the piercing stare Juan cast as an officer folded him into the back of a police car is engraved in her mind eternally.

When Officer Carlos Guevara questioned Susana, she couldn’t keep silent any longer.

“He threatened to have me deported if I told anyone; he’s been forcing me to have sex with him for two years.”

As Susana was transported to the Roxcy Bolton Rape Treatment Center, she nervously slid her fingers along the spiral binding of her notebook — one of the few possessions she carried with her and where her story would live until she gained the confidence to share it.

The officers had taken Juan back to the station, where he sat in a conference room uncuffed and waiting to be interviewed. Officer George Otero arrived at the Hialeah Police station and relieved the detective sitting with Juan.

As he entered the room, Juan began making a number of spontaneous statements without being questioned.

“I was helping her,” Juan told Otero. “She came on to me.”

Otero later documents in the police report that Juan continued making unwarranted statements, saying he had been set up and Susana, who was 17 years old at the time, was mature for her age.

Within several days of his arrest, however, a rape kit confirmed that traces of Juan’s semen were found inside Susana. According to the Miami-Dade Police Department’s Forensic Bureau, the rarity of said DNA profile exceeds 1 in 320 billion.

Still, to most of Susana’s paternal relatives, evidence was not as convincing as word of mouth. They knew Juan, or at least they thought they did; his testimony alone was enough to rid him of any fault and to demonize Susana.

In their eyes, Susana has always been troubled, a remark that would often be utilized in an attempt to refute whatever findings were brought to their attention.

Her paternal relatives’ disbelief, coupled with their misplaced anger, planted a wedge between Susana and her extended family, leaving both parties in a state of turmoil.

“Unfortunately, he didn’t think that his decisions would hurt anyone besides me,” Susana said, lifting her hands to wipe away the tears swelling in her eyes. “I’m sorry that it did.”

Leslye Matta, Juan’s wife, did not return The Hawkeye’s request for an interview. The Matta family has declined further requests to comment on the charges.

• • •

Susana Matta, 19, photographed outside of HCC’s Ybor campus.

On Feb. 27, 2020, Juan was sentenced to 20 years in prison for one count of sex with a familial child and one count of contributing to child delinquency. He is expected to be released in 2040 and will be on probation until 2050.

A month after Juan’s sentencing hearing, Susana nears the end of her freshman year of college.

She has come to realize that survival is much more than the persistence of flesh; it is an attempt to grow beyond the pain endured.

An attempt she’s made by maintaining an active role in her community.

Susana regularly feeds the homeless, advocates for social justice and participates in protests supporting the rights of immigrants and other minorities.

She has acquired a temporary work permit through the Violence Against Women Act and is employed as a legal assistant at a local law firm.

Susana aspires to one day become a lawyer and help others facing circumstances similar to her own.

Mary Volkman • May 12, 2020 at 8:54 am

Heart wrenching but inspiring! The blessing in Susana’s story is the inspiration to help others. It isn’t for nothing that she made it to the U.S. and survived familial rape and abuse.